Dear Readers,

Each time a woman writes her truth, she cracks open a world that was not built for her.

“Was not the world a vast prison, and women born slaves?”

― Mary Wollstonecraft, Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman

The most fundamental truth of women’s life writing is its rebellious pulse — its refusal to conform to the masculine tradition of autobiographical writing, established by figures like Saint Augustine in his Confessions (4th century A.D.), where life is narrated in retrospect from a position of authority and sanctity. When women like Mary Wollstonecraft dared to write their lives, they subverted the patriarchal language itself, turning a tool of oppression into an instrument of defiance. Across the world, Indian women, contemporaries of Wollstonecraft, were forging their insurgent narratives — breaking not just the silence but the very structures designed to contain them. They dismantled the illusions of gender hierarchy, caste dominance, and the rigid, violent separation of private and public lives that imprisoned them.

"Well, I was like a caged bird. And I would have to remain in this cage for life. I would never be freed.”

— Rashsundari Debi, (Amar Jiban)

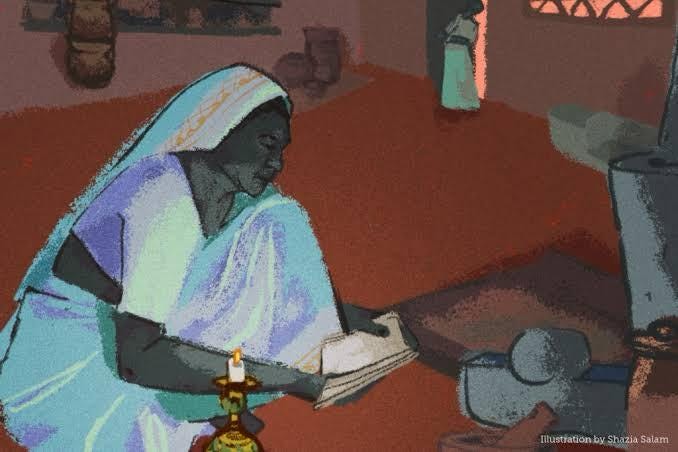

Rashsundari Debi’s Amar Jiban (1868) is a profound act of historical courage — a flame of dissent kindled in a world that conspired to keep women voiceless. In 19th-century India, where Western education became the guarded privilege of upper-caste men, women, and Dalits were deliberately barred from literacy. Patriarchy, now reinforced with the imported Victorian morality, sought to trap women within invisible walls. Rashsundari, bound within the suffocating confines of the andarmahal and buried under endless, Sisyphean household labor, defied the violence she was taught to internalize. The very act of learning to read and write was, for Rashsundari, an act of secret, sacred rebellion — one undertaken under the looming fear of losing caste, of social death, and of widowhood.

In a world shaped by masculine ideals of power—where triumph is measured by nuclear strength and conquest—the quiet miracle of a woman learning to read in the confines of her kitchen remains an act of profound resistance, too often overlooked and uncelebrated.

"At night, when everyone slept, I would light a lamp and read. I had to hide my desire, like a thief hides stolen treasure."

Pandita Ramabai’s work strikes a similar chord of fury and sorrow. In The High-Caste Hindu Woman, she reveals:

"The woman’s court is situated at the back of the house, where darkness reigns perpetually. There the child-bride is brought to be forever confined."

But Pandita Ramabai refused to remain in that darkness. She shattered the barriers between private and public life, claiming for herself the right to travel, speak, and learn. With fearless resolve, she journeyed from Kanyakumari to Kashmir, Karachi to Calcutta, engaging in intellectual discourse that was systematically denied to women.

"My soul thirsted for freedom, for knowledge, for spiritual light; and I am determined that I must seek them at any cost."

— Pandita Ramabai’s American Encounter: The Making of a Modern Hindu Woman by Meera Kosambi (2003, quoting Ramabai's letters and speeches)

In 1878, when she lectured purdah-clad women on the very Shastras that had been used to bind them, she was honored with the titles "Pandita" and "Saraswati" — yet she sought a secular, liberatory knowledge that transcended Hindu orthodoxy. Her acts of defiance were many: her marriage to Bipin Bihari Medhavi, a Shudra, shattered caste taboos and reclaimed love as a feminist act of resistance.

"Real reform does not commence with the mere enactment of laws; it begins with the awakening of the soul."

— "The High-Caste Hindu Woman" (1887)

Pandita Ramabai’s story reveals the infinite possibilities that are revealed when women leave the confinement of caste, home and savarna morality.

The remembrance of women’s histories is vital for imagining feminist futures that continue to resist cis-Brahmanical patriarchy. These figures remind us that the feminist movements of the Global South are built on the audacious dreams of those who defied norms—women who performed quiet miracles, sometimes from within the strict confines of home, and sometimes by boldly stepping beyond them. Their lives are not relics of the past, but living testaments to the resilience, courage, and radical imagination that shape our collective struggle today.

— Written by Anchal Soni, ULR

We are so excited that the April Edition of Matchbox is here!

It’s a powerful collection of voices, ideas, and visions that explore identity, art, memory, womanhood, and resistance. From intimate interviews and lyrical poetry to fierce fiction and quiet reflections, there’s so much to dive into.

Ashwani Kumar’s Kolkata, Longing & Belonging and other poems offer a poetic journey through desire, memory, and the rituals that shape us.

Ravi P. Viswanathan shares an excerpt from his book Anna: The Queen of Hearts—a moving story of quiet strength and service of Anna Lopez’s life of volunteering.

Anisha Lalvani’s excerpt from Girls Who Stray captures the chaos of young womanhood with sharp honesty. Check out Anushree Nande’s review of the same as she reveals how the novel subverts the crime plot to examine gender, desire, and alienation.

Sneha Krishnan reflects on contemporary Indian films through an intersectional feminist lense and examines films such as Humans in the Loop, Angammal and more.

Visual artist Rithika Merchant talks to Athmaja Biju about her latest exhibition Pillars of Fruit and Bone at TARQ and delves deep into her artistic process and thought.

Kabir Deb revisits six early Irrfan short films released by FTII. These raw, poignant works show the emotional genius of an actor before he became a global icon.

Tansy Troy in Conversation with poet Basudhara Roy discusses Roy’s creative process and feminine experience of love.

In his review of Anemone Morning and Other Poems, Kabir traces Gopal Lahiri’s poetic urgency. These are quiet poems of freedom, vulnerability, and yearning in a vast, unknowable world.

In an essay, reclaiming the legacy of P.K. Rosy, Malayalam cinema’s first Dalit heroine, Athmaja Biju offers a moving tribute to survival and erasure. Check out her review of Bhavika Govil’s Hot Water, A gentle yet piercing novel about mothers, children, and the weight of secrets.

We hope this month’s issue gives you much to reflect on—and feel. Thank you for reading and sharing.

Stay close with us on Instagram & X for upcoming calls for submissions and opportunities.

With love,

Athmaja Biju

Team Usawa

Ooof the first sentence 🤌🤌🤌

This post reminded me how far along we came and how much more still left. Thank you for writing this piece on an important movement of Indian Feminist history 🫶🏼